The Caribbean has thirteen sovereign states, each with distinct rights and protections for the LGBTI community. However, like many nations with a history of colonization, the views of the LGBTI community in this region are mostly unfavorable.

European countries heavily colonized the Caribbean. Along with their colonial rule, the Europeans brought Christianity, which they integrated with the laws and culture of Caribbean regions. Despite these colonial powers not physically residing in these states, some European countries still served as a head of the state, making them a part of the Commonwealth realm. Therefore, conservative views and practices are still integrated, further endangering LGBTI communities. Some nations have begun cutting ties with their head of state, such as Barbados, to fight these incriminating views.

On November 30th, 2021, Barbados became the first region to become a republic since 1992, officially cutting ties with Britain as its head of state. Barbados will remain within the Commonwealth of Nations; however, the nation is now led by a new head of state and is reforming its constitution as a new republic. This is monumental, as it brings new possibilities for change within Barbados’s legislation and civil society and further influences other Caribbean regions to follow suit.

Following this transformation, the parliament of Barbados made many changes. First, a new five-article charter was presented to the Barbados government, which, for the first time, referenced a person’s human rights concerning their sexual orientation. The House of Assembly and Senate approved this charter but has yet to be legalized. However, activists are in hopes that this document will influence future legislation. In addition, On December 12th, 2022, the High Court of Barbados issued an oral ruling decriminalizing same-sex relations, becoming the third Eastern Caribbean nation to do so, following Antigua and Barbuda (July 5th, 2022), and Saint Kitts and Nevis (August 29th, 2022).

These were pivotal moments as they came from countless local and regional efforts that challenged these anti-LGBT legislations, which were led in part by Eastern Caribbean Alliance for Diversity and Equality (ESCADE). On October 31, 2019, ESCADE announced the launch of its five-country litigation strategy that was created to challenge the criminalization of same-sex activity among adults in the Caribbean region. The goal was to gather cases and file them to the courts at an opportune time. This was very successful. For example, the complaint filed in Saint Kitts and Nevis stated that Sections 56 and 57 of the Offenses Against the Person Act violated constitutional rights, and the courts agreed. This was similar to the decision in Antigua and Barbuda, as a case initiation by a gay man, along with the help of the Women Against Rape (WAR) organization.

As expected, this was met with backlash. This was met with backlash as the Evangelical Association of Saint Kitts, under the umbrella of the Evangelical Association of the Caribbean, attempted to uphold this case in court through an affidavit.

Despite this reaction, this landmark ruling in Saint Kitts and Nevis became a regional trend, following the nations of Antigua and Barbuda, Trinidad, and Tobago, which decriminalized homosexuality in 2018, and Belize in 2019, eventually followed by Barbados in 2022.

However, the work still needs to be completed. Seven Caribbean nations still criminalize same-sex relations: Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. In addition, Barbados still does not allow the changing of gender and the recognition of non-binary gender along with Satin Kitts and Nevis and Antigua and Barbuda. There is also no required protection from LGBTI discrimination, along with employment and housing discrimination, in Barbados and Saint Kitts and Nevis; however, Antigua and Barbuda have illegalized these forms of discrimination.

It is also important to note that many of these political changes were slowed down due to the 2020 global pandemic; however, as proved by Barbados, the push for these changes is still on the rise.

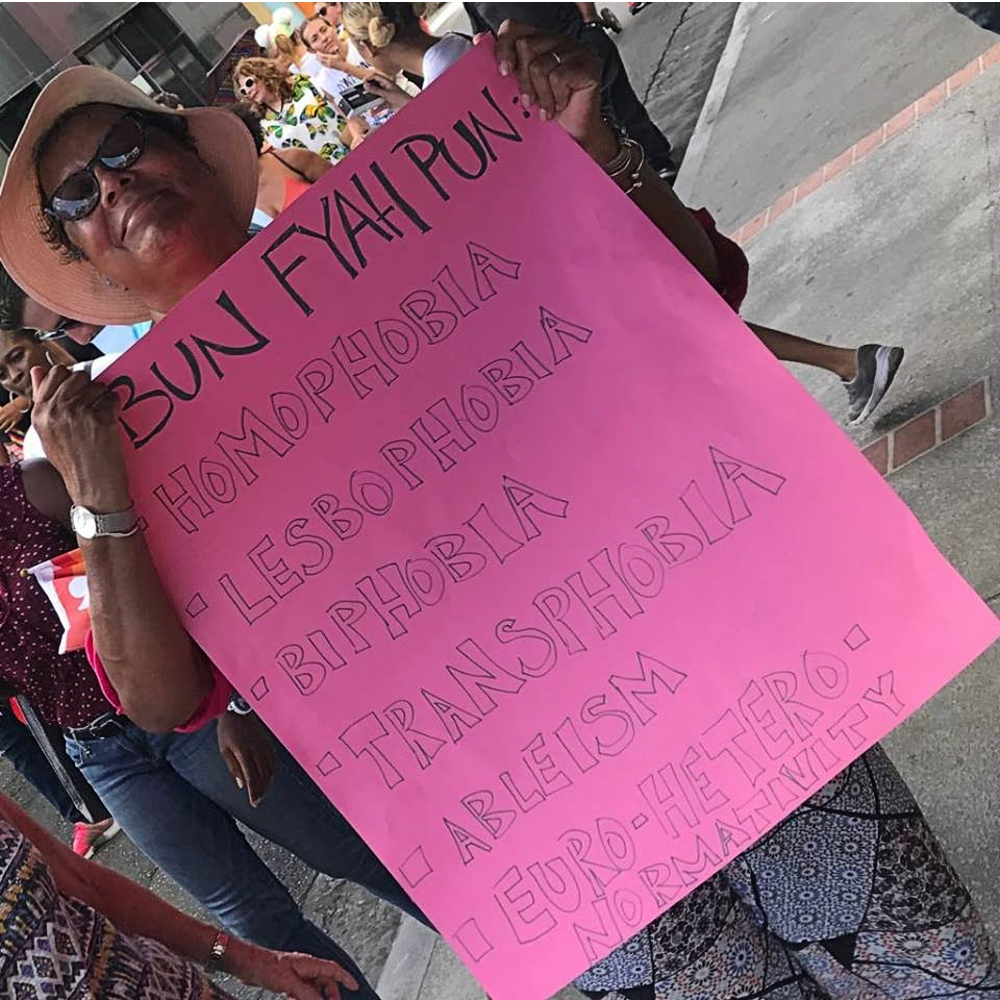

As seen, the changes in legislation regarding LGBTI rights are staggered but in great progress, illustrated in the chain reaction of changes occurring in this region, especially in a short amount of time. If Barbados and its neighboring nations continue to follow suit, the rights and freedom of LGBTI people could be guaranteed in all Caribbean regions. Lastly, all this progress would not have occurred without local and regional efforts. Organizations like ESCADE, WAR, and local movements are among the main reasons why such progressive changes have occurred in the Caribbean. Although in comparison to other nations, these steps may seem small, in the context of the history of Barbados and its neighboring regions, this is a monumental step in creating lasting progress for LGBTI communities in the Caribbean.